Mondays were paydays. And they were all the same.

Matt Kluckowski would await his direct deposit from Applebee 's, where he worked as a cook. Then, grab cash at the ATM, score dope at the trap house, mix up and tie off.

Sitting on the couch, the left-hand employs the slim needle that pierces the right arm. Always in the same spot, confessed by the scarred blue vein traversing the shallow crux.

The plunger depressed, euphoria delivered. All familiar.

But the odd, grey-tinged heroin Kluckowski scored on Sept. 7, 2015 had him in an unfamiliar spot: plunging face-first down a long flight of stairs, dying.

He had overdosed.

Someone called 911. Paramedics found an unresponsive Kluckowski at the bottom of the stairs. They injected him with four doses of naloxone, a drug that reverses opioid overdoses. Then, they hit him with a heart defibrillator.

Nothing.

They hit him again. And again.

No heart rate. No breathing. No brain activity.

Paramedics pronounced him dead.

“They were bringing me to wherever they bring dead people. No lights, no sirens,” Kluckowski said. “Then they heard a loud gasp out of me — and I started breathing on my own again.”

The naloxone took effect and brought Kluckowski back to life.

Read more: Sunny Daze, Inside South Florida's Opioid Crisis

The next day, Matt Kluckowski got on a plane from Portland, Maine to South Florida to get treatment. Now more than two years sober, the 26-year old works as an addiction counselor at Rebel Recovery in West Palm Beach.

A miracle drug

Naloxone saves lives every day in South Florida. It kicks opioid molecules off receptors in the brain, reviving overdose victims and allowing them to start breathing again.

The drug is not new. It’s been around since the 1960s, discovered around the same time as ibuprofen. For decades, it cost less than $5 per dose. There’s no other drug that can reverse an opioid overdose fast enough to save a victim’s life.

“It truly is a miracle drug,” said Delray Beach Fire Rescue Chief Neal De Jesus. “We can’t do without it. It’s either buy the drug and administer it to save lives, or don’t buy it and watch people die.”

On average, 115 Americans are now dying every day from opioid overdoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As first responders in South Florida — and across the country — need naloxone like never before, the escalating cost of the drug is socking it to taxpayers, according to a new WLRN investigation.

Costs skyrocket

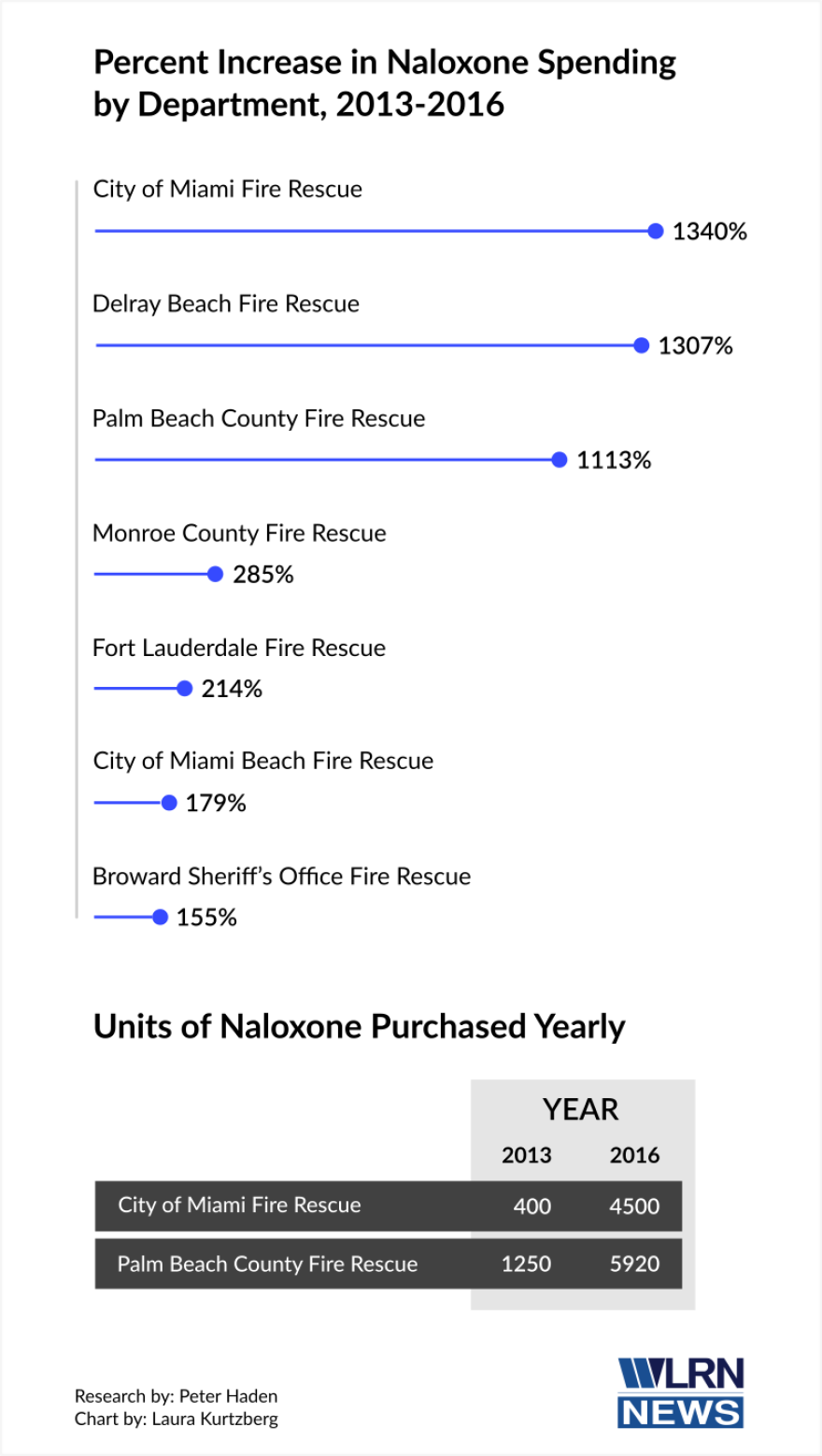

A WLRN analysis of eight major South Florida fire rescue departments shows spending on naloxone soared between 2013 and 2016.

Delray Beach Fire Rescue used to spend $2,100 on naloxone. Now it spends 14 times that.

Miami Fire Rescue used to spend $3,600. Now, it’s also 14 times that amount.

And Palm Beach County Fire Rescue’s naloxone bill went from $18,000 to $205,000 — an increase of more than 1,100 percent.

More overdoses explain part of the rising expense.

But the cost of life-saving naloxone has also soared. Paying the price: police, fire rescue and EMS agencies. And that’s causing concern in Congress.

“The thing that I think bothers me so much about naloxone is that the price was jacked up — I mean, big time — at the very time when the first responders and others were trying to get it,” said U.S. Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., at a Nov. hearing on a federal report describing naloxone shortages for some rescue agencies.

According to records obtained by WLRN, Miami Fire Rescue paid $9 in 2013 for each dose of naloxone made by California-based Amphastar Pharmaceuticals. Three years later, the same dosage cost $40, a price jump of nearly 350 percent.

That hurts if you’re buying one dose of naloxone. In 2016, Miami Fire Rescue bought 4,500 doses.

“The best part of wearing a Miami firefighter uniform is that we don't put a price tag on saving someone's life,” said Miami Fire Rescue EMS Chief Robert Hevia.

Whatever the price of naloxone, the department has to pay it.

“Our mission is quite simple: to save lives and protect property,” said Hevia. “The fire department doesn’t spend its time splitting pennies. We view it as the cost of doing business.”

A fair price?

When you have a product that can save someone’s life, how do you decide what is a fair price?

No doubt the law of supply and demand is having an effect. But take the example of Kaléo Pharma.

The company makes an emergency autoinjector called Evzio, marketed to individuals rather than first responders. It’s about the size of a phone and gives real-time instructions anyone can use. The delivery device hit the market four years ago, but the drug it injects is 1960’s naloxone.

In 2014, the retail cost of a kit with two single-use Evzio autoinjectors was around $600. But three years later, that same kit cost more than $4,000.

The steep cost increases for naloxone have drawn calls for price transparency.

“We need to know where the price is coming from,” said Dr. Scott Kjelson, Professor of Pharmacy at Nova Southeastern University. “They increased, what — 100, 200, 300 percent? How? We need to know how.”

For those inclined to think federal regulators may have answers, think again. A disclaimer on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s website says:

“The FDA has no legal authority to investigate or control the prices charged for marketed drugs,” the website reads.

But members of Congress and state Attorneys General? They can investigate.

In August, Sen. Claire McCaskill, D-Mo., sent letters to four drug companies that make naloxone, asking them to provide details about the discount programs the offer to rescue agencies. It's part of an ongoing probe McCaskill launched in 2016 with Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, into rising drug prices.

“What is a pharmaceutical company doing, making the price unreachable for the very drug that can save lives?” said McCaskill to reporters on Capitol Hill.

And if this sounds familiar, it is.

Another life-saver: the EpiPen

In 2016, Congress demanded answers from pharmaceutical manufacturer Mylan for the soaring cost of its EpiPen.

The EpiPen is an emergency autoinjection device, like Evzio. This one reverses life-threatening allergic reactions. And, like Evzio, it was essentially the only product of its kind on the market.

Between 2009 to 2016, Mylan jacked the price of a kit with two EpiPens from $100 to $600.

There was a public outcry, particularly from the elderly and parents of allergic children.

Mylan CEO Heather Bresch testified before the House Oversight Committee.

"Looking back, I wish we had better anticipated the magnitude and acceleration of the rising financial issues for a growing minority of patients who may have ended up paying the full price or more," Bresch said in her testimony. "We never intended this."

Committee members excoriated Bresch.

“It’s disgraceful what’s going on here,” said Rep. Stephen Lynch, D-Ma. “The blatant disregard you have and disrespect you have for people who desperately need this medication. The cost increases are up 1,151 percent... I think it’s disgusting.”

A different stigma

There hasn’t been the same public outcry over naloxone as there was for the EpiPen. Nova Southeastern University pharmacy professor Scott Kjelson thinks he knows why.

“There are still people who think people that use drugs deserve to die,” Kjelson said. “That’s the difference. It’s a different stigma.”

Amphastar Pharmaceuticals did not respond to multiple interview requests.

A spokesperson for Kaléo Pharma, the company that makes the Evzio autoinjector, issued an email response.

It points out that through Kaléo’s direct-delivery service, many patients can get Evzio deeply-discounted or free.

The company says it has donated nearly 300,000 autoinjectors to first responder agencies and public health departments. It says more than 5,000 lives have been saved by those donated devices.

In regard to Evzio’s current $3,800 list price, Kaléo says no patient actually pays that. The company says it has to set the price that high, so lots of people can get Evzio for free. Follow up requests did not clarify what that means.

The company did acknowledge the current healthcare system “is flawed.”

** Note: This story has been updated to reflect that Kaléo does not sell the Evzio autoinjector to first responders. The company says to date, it has donated 6,000 Evzio devices to first responders, public health departments and nonprofits in South Florida.