There comes a moment in every political upheaval when the sound and fury of protests have to hook up with the clarity and practicality of platforms.

For anti-government demonstrators in Venezuela, that moment's arrived.

Since Feb. 12, the oil-rich but deeply divided country has been rocked by student-led unrest. Protesters are lashing out at President Nicolás Maduro’s heavy-handed socialist government and its inability to solve a raft of economic and social crises, including South America’s worst inflation and murder rates.

But after two weeks of street clashes that have seen more than 15 people killed – and now have U.S. pols like Florida Senator Marco Rubio lining up to slap sanctions on Maduro’s government – Maduro doesn’t look much closer to leaving the Miraflores presidential palace than he did on Feb. 11.

And that has a growing number of Venezuelans both there and here in South Florida – home to the U.S.’s largest Venezuelan community – asking an apt question: Was toppling the regime, Ukraine-style, really the immediate purpose of these protests in the first place?

Mario Di Giovanni, a 25-year-old Venezuelan who came to Miami three years ago, is one of them. “I think people need to bring their feet down a bit,” he told me this week. “This shouldn’t be about just a change of government but about a change of how we see things in Venezuela and how we do politics in Venezuela.”

Which is probably what the protests and their leaders need to articulate to Venezuelans, but haven’t.

RELATED: Venezuela's West Side Story: Why Street Protests Aren't Likely To Topple The Regime

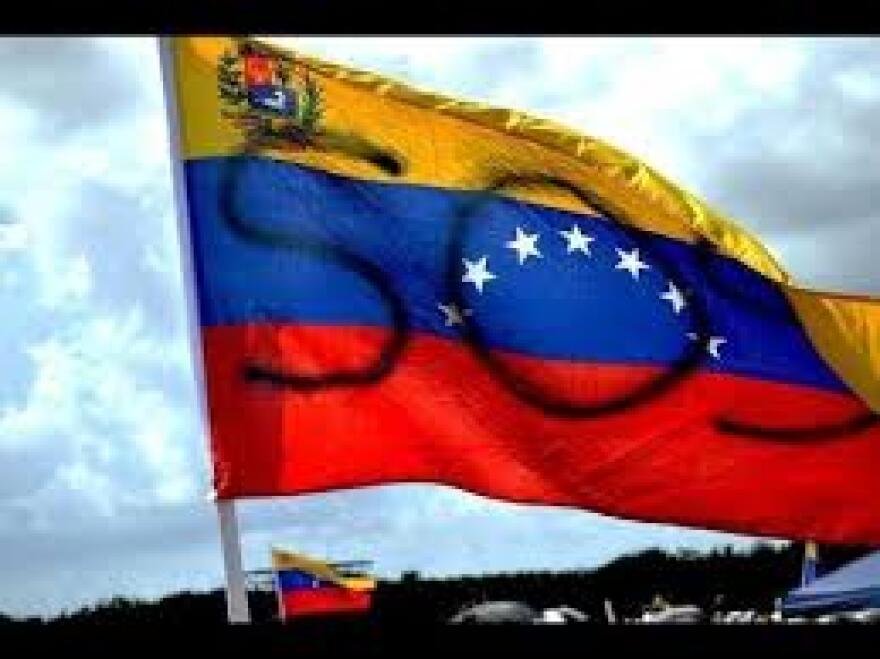

Di Giovanni is a committed anti-Chavista – the Chavistas being Maduro’s party, followers of the founder of their left-wing revolution, Hugo Chávez, who died a year ago next Wednesday. Di Giovanni helps head up causes here like Voto Donde Sea, a diaspora voter-aid organization, as well as the large SOS Venezuela rallies being held now in enclaves like Doral.

But ex-pats like Di Giovanni tell me they worry nonetheless about urealistic expectations – about a widespread assumption that the protests’ objective is all-out, overnight regime change. The more viable aim, they say, should be a change in the Chavistas’ failed policies and authoritarian practices.

This is about a change of how we do politics in Venezuela. -Mario Di Giovanni

That’s the kind of strategy point the Venezuelan opposition can ponder during the current lull in the unrest – as Maduro holds a “national peace conference” in Caracas and many Venezuelans head to the beach for the Carnival holiday.

Opposition leaders have refused to attend the peace gathering until Maduro’s government releases arrested protesters, including a former Caracas mayor, Leopoldo López. They also fear Maduro simply wants to turn the meeting into one long rant against the protests – and they were borne out as el presidente kicked off the proceedings on Wednesday.

The protesters, Maduro insisted in his opening remarks, “are not out there burning barricades because of milk shortages. This is violent insurrection meant to bring down the republic” with U.S. backing.

Maduro’s also extended next week’s Carnival break to include Thursday and Friday of this week, which could further dilute the size and intensity of the demonstrations.

GOVERNMENT BRUTALITY

But while the peace conference may help Maduro regain some leverage, it’s also a sign of how much of it he’s lost in this emergency. And how much damage repair his international image needs.

Granted, the government has hurt the opposition’s ability to convey a more unified project with its campaign to stifle independent print and broadcast media. While social media like Twitter are good for calling people into the streets, they’re not so useful for convincing them of your programs.

But social media have been effective at disseminating images of government brutality. “We can see really what’s the nature of this regime,” says Di Giovanni. “We have seen all sorts of pictures, videos on the National Guard beating up students, shooting at students.”

Not that every protester has been a Ghandi-esque saint during this drama, either. But even government prosecutors this week charged five Venezuelan intelligence agents with murder in connection with two of the protest shooting deaths. That was a stunning admission on the part of Maduro, who has repeatedly insisted the protesters (including López) were to blame for the killings and scores of serious injuries.

Even so, government opponents like Di Giovanni know that Maduro can still count on his base among Venezuela’s poor to remain in power – and that they need to build more genuine bridges to those working-class voters if the protests are going to have legs.

Early on, says Di Giovanni, “I was seeing that maybe the [protesters] weren’t considering that point. But in the last few days I know that they really have been trying to reach out to all these social classes. Because we’re not going to get anywhere without them.”

Especially after Carnival.

Tim Padgett is WLRN's Americas editor. You can read more of his coverage here.