Pope Francis didn’t have to say it. He let the timing say it for him.

The pope this week named Haitian Bishop Chibly Langlois as one of 19 new cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church. In the process, he all but declared a shift in clerical power on the large Caribbean island of Hispaniola. And he may also have delivered a rebuke to the Dominican Republic, the country that shares that isle with Haiti, and to the D.R.’s controversial cardinal, Nicolás López.

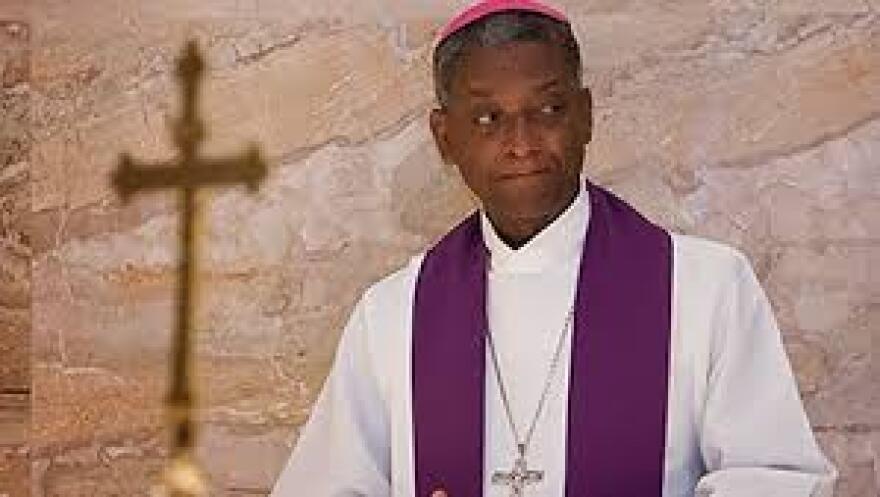

Langlois’ selection is thick with the sort of reformist symbolism that’s become Francis’ trademark. Haiti, a predominantly black republic, is the western hemisphere’s poorest country; and until now it has never had a cardinal – one of the powerful “princes” of the church – even though about 85 percent of its population is Catholic. The pontiff announced Langlois’ elevation on Jan. 12, the fourth anniversary of the 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti and killed more than 200,000 people.

RELATED: New World Pope Challenges Old World Church: Francis Is Top LatAm Story In 2013

Langlois, speaking in Creole, said this week that his appointment “shows the pope has a fondness for Haiti and the Haitian church.” But Miami Archbishop Thomas Wenski got more to the heart of the matter: The pope’s move, Wenski said, “will bring much-needed attention to Haiti and the plight of its people.”

Like Haiti, Langlois is a profile of the underdog Francis wants the church to put front and center again.

Like Haiti, Langlois himself is a profile of the underdog Francis wants the church to put front and center again. Langlois was born into poverty in southeast Haiti, and he’s admired for a common touch that shone most after the earthquake. That’s perhaps a big reason the pope selected him even though he represents only the diocese of Les Cayes and not one of Haiti’s larger archdioceses, such as the capital, Port-au-Prince.

What’s more, the 55-year-old Langlois is relatively young. Reformers anticipate he'll bring the sort of fresher, more modern perspective Francis has signaled for his papacy.

CARDINAL SINS

Langlois, in other words, is a stark contrast to the 77-year-old Cardinal López, who seems not to have gotten any of the recent papal memos. Last summer, when Francis was telling reporters that it’s not for him “to judge” gay people – a remarkably humane change in Vatican tone – López was publicly venting his irritation with the appointment of an openly gay U.S. ambassador to the Dominican Republic, James Brewster, by using the word maricón, Spanish for “faggot.”

Nor has López appeared to pick up on the Holy See’s call to watch the little guy’s back. Last September the Dominican Republic’s high court ruled that anyone born in the D.R. after 1929 can have their citizenship stripped if their parents were undocumented immigrants or non-Dominicans. Most affected by the decision: about a quarter million Haitian-Dominicans, who are now left stateless. The international community has decried the ruling, and Haitians say it's racist. But López recently called the ruling’s critics “liars and charlatans.”

St. Vincent and Grenadines Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves told WLRN that during his December meeting with the Pope at the Vatican, the pontiff agreed that the Dominican court decision is “unacceptable.” If that’s true (the Vatican hasn’t contradicted Gonsalves) it’s reasonable to conclude that neither the D.R. nor López was high on Francis’ Christmas-card list.

López has also blamed the clerical sexual abuse scandal in the United States on what he calls an incursion of “effeminate” priests, and he once insisted priestly pedophilia could never happen in the Dominican Republic. But these days el cardenal is having to apologize to Dominicans for abuse cases in his own archdiocese.

As a result, calls for López’s resignation – including those from luminaries like Peruvian Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, who can hardly be called a bleeding-heart liberal – are growing louder.

Not that the Haitian church is a progressive model, either. Reproductive rights advocates say its fervent opposition to birth control has encouraged an inordinately high pregnancy rate in Haiti – and in turn one of the world’s highest maternal mortality rates, more than 600 per 100,000 live births, according to the Pan-American Health Organization.

But even if Langlois probably won’t buck the Vatican’s anti-contraception doctrine, he may well follow Francis’ recommendation that the church cease obsessing on the issue. If so, that could loosen political resistance to broader birth-control access in Haiti.

For now, Haitian Catholics are simply taking heart in the rise of their first priestly prince – and perhaps in the falling fortunes of the old one next door.

Tim Padgett is WLRN's Americas editor. You can read more of his coverage here.