Nearly two years into Miami-Dade Schools’ signature alternative-to-suspension program, it’s hard to measure the impact of the heavily touted Student Success Centers.

A $45,000 evaluation report, first obtained in draft form by WLRN in December and made public during a school board meeting in February, offers a look at demographics and basic data on roughly 400 of the students who attended success centers in 2015-2016. More than half the students were black; nearly two-thirds were boys.

The program was designed to allow schools to remove disruptive students from the classroom without sending them home unsupervised, a common practice until the district banned out-of-school suspensions at the start of the 2015-2016 school year.

The evaluation was intended to measure the Student Success Centers’ impact on “student attendance... academic performance, and school behavior,” along with recidivism—the likelihood that students with behavioral infractions will repeat them.

The report shows how long students spent at success centers, what schools they came from (Miami Norland High School and Andover Middle School top the list), and includes interviews with the staff who supervised them there.

NO TEACHERS, NO STUDENTS

But, as School Board Member Steve Gallon noted at the board meeting in February, “Teachers and principals were not included. Why was that?”

Deputy Superintendent Valtena Brown said the timing of the evaluation, conducted over the summer, made it difficult to get input from school staff. But principals are year-round employees. Gallon was one of those principals for 10 years. He said in an interview that administrators contact teachers over the summer all the time.

“That dog won’t hunt,” he said.

“If you’re not talking with the teacher at the school that sends the kid to get a sense of his or her behavior that prompted it,” Gallon said, “if you’re not talking to the assistant principal or the principal to talk about the practices in school, then you’re not really dealing with the root causes.”

Students weren’t interviewed for the report either.

“The program was designed to meet the needs of students. We really have to hear from them whether or not that’s happening,” said Amir Whitaker, an attorney and researcher who has represented Miami-Dade students and has taught in local high schools. Whitaker now analyzes student discipline data at the Civil Rights Project at UCLA.

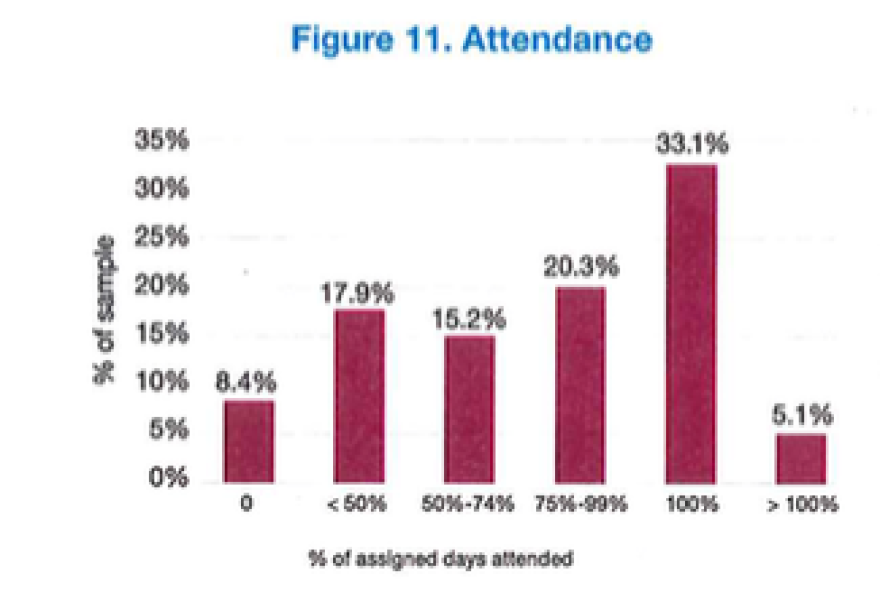

One finding in the report was that just 33 percent of students attended success centers the whole time they were supposed to. Students at success centers fill out exit surveys about their experiences administered by the district when they leave, but those weren’t included in the evaluation.

“If that voice isn’t included,” Whitaker said, “it really raises more questions than it answers.”

Gallon also questioned why just four parents and caregivers, representing three students, were interviewed when the overall sample included nearly 400 students. None, he pointed out, were parents of middle schoolers, in spite of the fact that middle schoolers represented more than half the students in the sample who attended success centers.

District staff didn’t respond to multiple requests for an interview for this story. In response to a records request, they said they did not have any minutes or notes from the meeting where the report was presented as a draft and had no written communication with the researcher regarding the report’s limitations.

WLRN spoke with the researcher, Sandra Williams of Q-Q Research Consultants, about the report. She did not make herself available for a taped interview. Previously, she told WLRN that limitations in the district’s own data—attendance records for success centers were kept by hand during the first year—made it time-consuming to merge information on success centers with student records from sending schools. Both Williams and district staff said efforts to interview students for the evaluation did not work out.

In a recent meeting with the Miami Herald editorial board, Superintendent Alberto Carvalho acknowledged challenges with success centers—on attendance and getting kids their schoolwork. He also pointed out incremental changes made to improve the program, including offering access to school bus routes, designating liaisons for success centers at sending schools and increasing staffing.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE DATA?

But anything, Carvalho said, would be an improvement over the previous policy: “You get suspended, you’re out. You’re on the streets, you’re at home, nobody knows where you are,” he said. “The data are compelling. We went from dozens of thousands of students being suspended annually to, first year—4,500 students being referred to success centers.”

According to the district’s data, just under 14,000 students were suspended from school before suspensions were banned, while close to 4,000 were referred to success centers the following year. That’s a massive drop in the practice of removing kids from school for bad behavior. “Looking at the data, it could seem that Miami-Dade Public Schools has found a silver bullet or some kind of magic wand,” said Whitaker, the attorney.

It’s possible Miami-Dade Schools have gone through a huge culture change that would explain this data, said mathematician Rebecca Goldin. She runs a service through the American Statistical Association and the nonprofit Sense About Science USA that helps journalists make sure they’re reading data correctly.

But, she added, the evaluators “wouldn’t even know if that’s the case because they didn’t interview the students or their teacher subsequent to their experience.”

There are lots of possible explanations for the shift in discipline numbers, Goldin added, including the possibility that the practice of off-the-books suspensions is far more common than the data indicates. Or, she said, misbehavior could be being recorded in data not included in the report, like on the “referral” forms filled out by classroom teachers when an incident takes place.

READ MORE: School Suspensions Continue In Spite Of Miami-Dade's No-Suspension Policy

To see whether success centers are improving behavior and academic performance as intended, she said, the report could have looked at student grades once they went back to school, or the number of infractions seen in schools using success centers.

As it was, she said, there was “essentially no assessment of the benefit of the program” that could be justified with the quantitative data used in the analysis.

District staff noted at the February board meeting that their involvement in the evaluation was limited to a ‘data dump’ to Q-Q research to avoid interfering with the result. But, Goldin said, “There’s a kind of starting point analysis here that, it’s clear they wouldn’t have been able to answer those questions based on the data they have.”

Gallon said understanding how success centers are affecting school culture would require another evaluation altogether.

“We’re not trying to reduce suspensions. We’re trying to reduce acts of of defiance, disrespect, disruption, and danger,” he said.

In February, Gallon won school board approval for a task force to solicit feedback on the implementation of the program and offer recommendations for the future. An update is expected in May.