This obituary originally ran in Time Magazine.

Fidel Castro, the world's most revered and reviled revolutionary, has died in Havana at age 90.

Castro's legacy will be a source of fierce debate—one he often took part in while he was alive. Shortly after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, for example, Castro met with a group of journalists on a visit to Mexico. We pressed the Cuban leader repeatedly about the fall of communism until, chafing in his olive fatigues and the Yucatán humidity, he stopped stroking his beard and pounded his fist.

“Instead of asking me why communism failed in Russia,” Castro shouted, “why don’t you ask me why it hasn’t failed in Cuba?”

Here’s why:

We all acknowledged the successes of Cuban communism, especially healthcare and education. But we were all too aware of its larger failures, evidenced by Castro's dictatorship and the harrowing economic hardships crippling the island during that post-Soviet “special period.”

Communism hadn’t survived in Cuba. Fidel had.

His paternal charisma and paranoid security apparatus had. They were an alloy that couldn’t be broken by 10 U.S. presidents, one of whom Castro took to the brink of nuclear war in 1962. And they stifled any urge Cubans may have had to tear down their own Berlin Wall during his almost half-century-long rule.

Illness forced Castro, at age 79, to hand Cuba’s presidency to his younger brother Raúl in 2006. But even afterward, Fidel and his regime lingered, faded yet sun-baked into Cubans’ lives like the pastel colors of an old Havana mansion.

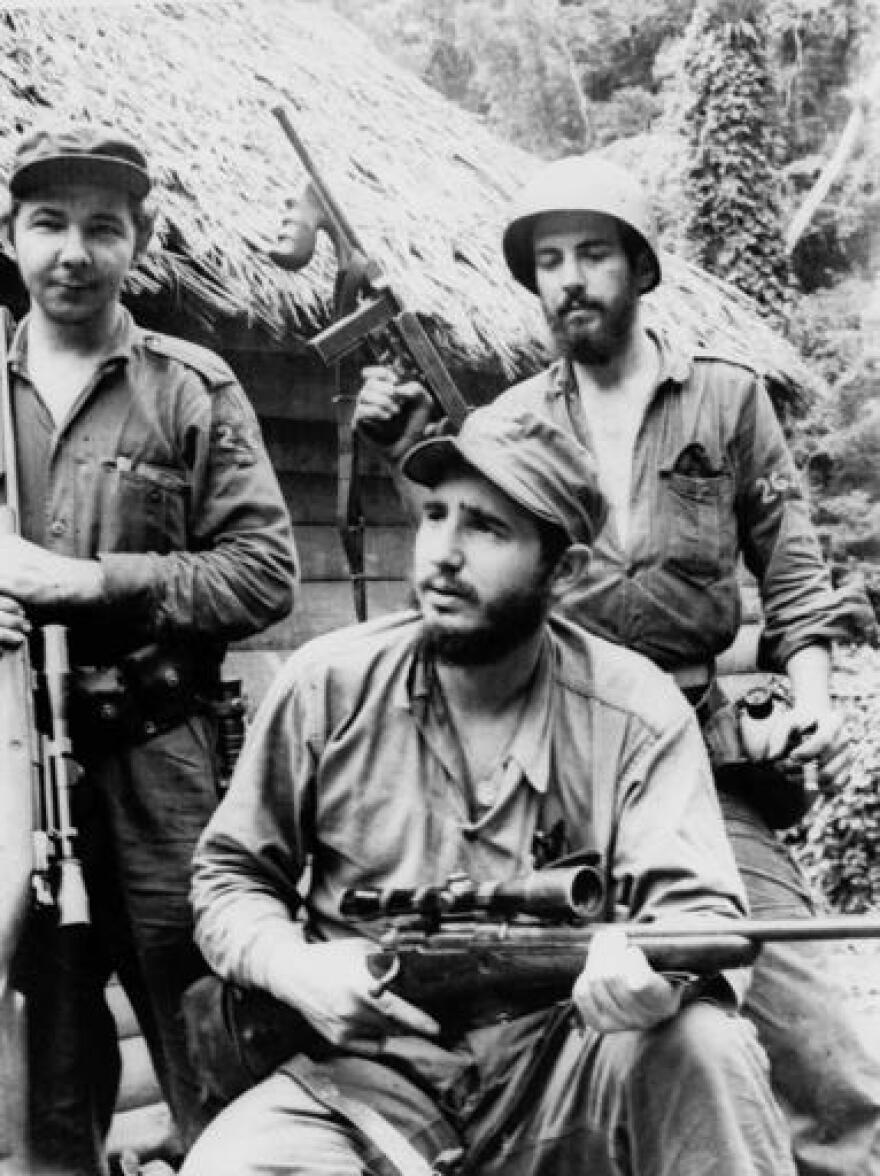

Raúl announced Fidel's death late Friday night. For the moment, the world will wax nostalgic about the younger, 20th-century Fidel—the torrid icon who did perhaps more than anyone to define The Revolutionary. He seared that picture into our imaginations with his cigars, the fatigues and the beard, with the hours-long speeches slinging Davidic defiance at his imperialista Goliath, the United States.

To millions of underdogs in the developing and developed worlds alike, Fidel was a tropical avenger who stood up to superpower in the name of social justice. He even had a sidekick, the late Ernesto “Che” Guevara, whose rock star portrait has so effectively promoted the rebel brand Castro commanded.

But most of Castro’s admirers didn’t have to live in Cuba. At the outset of his insurgency in 1953, Fidel insisted, “History will absolve me!” In some respects it will. But on balance it won’t. History will likely recall him as a tragic caudillo, a reminder that revolutionaries are usually a lot less romantic when they come down from the sierras and govern.

Contrary to the hyperbole of his exile enemies in Miami, Castro was not as blood-stained as other 20th-century despots like Stalin. And his universal health and education systems were widely lauded, despite being undermined by his chronic economic blunders and a U.S. trade embargo—which was itself a blunder that simply gave Fidel a convenient scapegoat.

Still, none of that absolves Castro of the Orwellian fear that stalked Cuba after he took power. It doesn’t excuse the thousands of dissidents who languished in his prisons or ended up in front of firing squads. Or the stultifying deprivation that still haunts the Caribbean island today and keeps launching desperate, often deadly raft voyages across the Florida Straits.

That was too a severe price to pay for free doctoring and schooling.

When the Cuban Revolution marched into Havana soon after New Year’s Day 1959—toppling the brutal, U.S.-friendly dictator Fulgencio Batista—it seemed the New World’s democratic ideals might finally take root in Latin America. Instead, Fidel imported Old World Marxism and its perverse notion that social justice is best delivered via the injustice of autocracy. It has left Cuba today as the only non-democratic country in the Americas.

To his fans, the fact that Fidel died with his revolution intact means he won. But the shambles it’s left in Cuba—and the fact that Raúl has had to adopt capitalist reforms and re-establish relations with the U.S. to keep it alive—signals a failure only Fidel couldn’t see.

Rise of a Revolutionary

Most revolutions are led by the middle class, and the Cuban who became a socialist legend was born into a bourgeois family in rural eastern Oriente province on Aug. 13, 1926. Fidel was the third child of Angel Castro, a tough, hardworking landowner from Galicia in Spain, and Lina Ruz, a Cuban housemaid. (Fidel was born out of wedlock, but his parents later married.)

Growing up near the battlefield where 19th-century Cuban independence hero Jose Martí died helped inflate Fidel’s sense of personal destiny. Though educated by Jesuits, he spent much of his youth alongside the laborers on his father’s finca (plantation), which engendered an empathy for the island’s browbeaten poor. And in backward and violent Oriente, he also learned the power of guns.

Castro’s real education began in 1945 when he entered the University of Havana as a law student and a self-proclaimed “political illiterate” who hoped “to have a line written about me in Cuban history.”

The school was a hotbed of radical, sometimes violent ideas competing to reform Cuba’s corrupt and chaotic society, which had only shaken off U.S. overseership of the island a decade earlier. (The U.S. wrested control of Cuba from Spain in 1898.)

Though for the moment he eschewed Marxism, Fidel came in contact with myriad left-wing groups and “talked incessantly about [a] revolution,” according to friends quoted in Tad Szulc’s 1986 biography, Fidel: A Critical Portrait.

But to Castro, the higher villain was the U.S., whose interventionist policies he increasingly blamed for the venal rot not just in Cuba but the rest of Latin America. After joining Cuba’s socialist Orthodox Party in 1947, he signed up for pan-Latin movements to free countries like the Dominican Republic from U.S.-backed right-wing dictators. In 1948 he fought alongside members of Colombia’s Liberal Party in the streets of Bogotá after the assassination of leftist leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán.

That year Castro also married Mirta Díaz-Balart, the daughter of a wealthy supporter of Batista, who had been Cuba’s elected president in the early 1940s. But in 1952, by now a lawyer, Castro saw his hopes of being elected to Congress crushed when Batista staged a military coup—an act that Castro said launched “a new revolutionary cycle” in Cuba that he would lead.

The next summer, on July 26, 1953, Castro gathered 170 insurgents, including his Marxist brother Raúl (who was born in 1931), and headed a quixotic armed assault on the Moncada army barracks in Santiago de Cuba in Oriente. It was a fiasco: the rebels were slaughtered, and Fidel and Raúl were captured shortly after.

Still, the raid made Castro a hero to downtrodden Cuban peasants when he stood trial that September. Eloquently conducting his own defense, frequently evoking Martí, he turned the case into a passionate indictment of not just Batista but all of history’s oppressors.

“My voice will never be drowned out,” he said. “I do not fear [prison], as I do not fear the fury of the miserable tyrant…Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me!” That speech, Szulc wrote, marked “the cornerstone of modern Cuban history ... the great revolutionary manifesto.”

Two years later, Castro was freed in a general amnesty. He and Raúl went into exile in Mexico, where they met Che Guevara, a young Argentine doctor steeped in the Marxism that Fidel was beginning to embrace himself—though Castro coyly maintained for years that he and his revolution were not communist.

Back home, Batista’s violent crackdowns on dissent, deepening poverty, a slavish deference to U.S. business interests and the growing involvement of mobsters in the island’s casino-fueled economy (see The Godfather Part II) made Cuba ripe for Fidel Castro’s next big act.

The Cuban Revolution

By the end of 1956, Castro and his compatriots decided they had collected enough guns and cash—some of it in the U.S., where Castro found numerous sympathizers—to launch a revolution. They paid $20,000 for a leaky wooden boat called Granma.

On Nov. 25, 82 armed members of the 26th of July Movement crowded aboard and, a week later, landed at a mangrove swamp in Oriente and came under intense fire from Batista forces. Only Fidel, Raúl, Che and 16 other rebels made it into the nearby Sierra Maestra to mount their insurgency.

But the image of a daring Castro rallying the countryside against a yanqui-friendly tyrant proved to be the uprising’s strongest weapon. As accounts of his Sierra Maestra heroics filtered out via correspondents like Herbert Matthews of the New York Times (whom Castro in 1957 may have tricked into thinking he had a guerrilla force of hundreds instead of dozens) the rebellion gathered strength until, in 1958, it had Batista’s 30,000-man army on its heels.

Its stunning success culminated on Jan. 1, 1959, when Batista fled the country. Castro traveled victoriously from Santiago to Havana, where on Jan. 8 he and his barbudos (bearded ones) took power. Fidel, as el máximo líder, took absolute power—but he’d learned enough double-speak to rationalize it: “The revolution,” he later said, “is a dictatorship of the exploited against the exploiters.”

In the U.S., the Eisenhower administration was quick to recognize the new Castro regime. Yet Washington’s early bridge-building attempts were futile; anti-U.S. sentiment was too deeply embedded in the revolution’s DNA. Castro warned there would be “an invincible resistance” to any U.S. interference in Cuban affairs. It was a fear, not always unfounded, that Castro would exploit to keep his dictatorial grip for the next half century.

He soon presided over a purge of anyone suspected of being a Bastista “henchman,” which sometimes meant anyone who disagreed with Fidel. The arrests, show trials and summary executions, in which Guevara played a particularly brutal role, further alienated the U.S. So did the expropriation of U.S.-owned properties and businesses, which helped send the first wave of Cuban émigrés to Florida.

Amid growing and hamhanded U.S. hostility to his government—his lore included all the bizarre ways the C.I.A. sought to assassinate him – Castro turned to the Soviet Union. At the U.N. in 1960, Castro and then-Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev exchanged a political bear hug that sent Washington into a cold-war panic.

The next year, a newly inaugurated U.S. President John F. Kennedy OK’d a half-baked C.I.A. plot for an invasion of Cuba by 1,500 Cuban exiles. They landed April 17, 1961, at the Bay of Pigs, but within a few days Cuban troops smashed the attack, which had little if any U.S. military support, leaving 100 exiles dead and almost 1,200 captured. The debacle handed Castro a triumph that helped consolidate his fledgling rule.

So much so that in October 1962, Castro, still only 36, felt emboldened to confront Kennedy on the far deadlier field of nuclear arms. Thus began the 13-day Cuban Missile Crisis. After letting Khrushchev install nuclear-capable ballistic missiles in Cuba, and after the Kennedy administration discovered them pointed at U.S. soil a mere 90 miles away, Castro urged Moscow not to back down as the two sides teetered on the edge of Armageddon.

According to Khrushchev’s memoirs, Castro even exhorted Moscow to “launch a pre-emptive first [nuclear] strike” if Washington carried out a naval blockade of the island. His erratic display helped frighten Soviet leaders into agreeing to remove the missiles, a move that infuriated Castro.

From Revolution to Rationing

By then, the U.S. had cut diplomatic relations with Cuba (President Barack Obama restored them in 2014) and imposed its unilateral trade embargo (still in force), including a ban on Americans’ travel to the island. Undaunted, Castro turned to fulfilling his revolution’s promises at home—and spreading its reach throughout Latin America and the Third World.

The 1960s and 70s were his glory days. “A revolution,” he announced in his typically martial idiom, “Is a fight to the death between the future and the past,” and he railed at capitalism as the source of the world’s miseries.

Cuba, with generous Soviet aid, did make remarkable strides in providing basic food and housing, cradle-to-grave healthcare and free and universal education. Castro meanwhile was celebrated as a counter-culture idol and a magnetic if messianic polymath. (No one enjoyed hearing Fidel hold forth on anything more than Fidel did.) Youths from Mexico to Malaysia pinned his poster on their walls alongside the Beatles, and some joined the socialist rebellions that he and his 250,000-man military supported in their countries.

Guevara was killed in Bolivia in 1967 on one such mission. Other Cubans spent years involved in Cold War proxy conflicts like Angola’s.

But by the 1980s, it was apparent that the Cuban Revolution had stalled on all fronts. Despite the domestic social advances, Castro never made his inefficient socialist economy work: Sugar cane harvests rarely met goals, well-educated engineers had little manufacturing to occupy them and the island was better known for all the rusty 1950s-vintage cars on Havana’s streets.

So many Cubans wanted to leave the country that in 1980 Castro, in a typical fit of pique at the U.S., let 125,000 of them inundate Florida in the Mariel Boatlift.

Abroad, his influence exhausted itself in the bloody civil wars of nearby Central America, where Washington was able to kibosh Marxist revolutions like Nicaragua’s (though history won’t likely absolve the Reagan administration’s conduct there, either).

Then, with the Soviet Union’s demise, Cuba was cut adrift economically. Castro seemed lost as well, unable to come to grips with the need for free-enterprise reforms that even Raúl, his military chief, urged him to adopt. Fidel’s delusional new war cry was “Socialismo o la muerte!”—socialism or death!—and for many Cubans it flirted too closely with fact.

The brothers kept the state afloat by allowing foreign investment in hotels and resorts; but that created what critics called tourism apartheid, a Cuba where foreigners ate lobster at swank restaurants while Cubans ate rationed meat once a week.

Yet even during that emergency “special period,” which has really yet to end in Cuba, Castro was able to keep a lid on dissent. The crisis, in fact, hardened his iron fist, forcing a world that once hailed his fierce anti-imperialist legacy to focus instead on his dismal human-rights record.

In 1996 he ordered fighter jets to shoot down two, unarmed small planes piloted by Miami exiles because they’d allegedly ventured into Cuban air space. (Four exiles were killed.) In 2003, after a leading dissident, Oswaldo Payá, embarrassed him by collecting tens of thousands of signatures in favor of a constitutional referendum on democratic reform, Castro accused scores of other dissidents of plotting with the U.S. against him and threw them in prison.

Fidel got an economic lifeline at the turn of the century when socialist firebrand Hugo Chávez took power in Venezuela. During his own 14-year-long rule until his death in 2013, Chávez became one of Castro’s most adoring acolytes and sent Cuba more than 100,000 barrels of cut-rate oil a day.

Intestinal surgery forced Fidel to cede the reins to Raúl in 2006, a move that became official in 2008. (In 2011 he gave up his last official title, head of Cuba’s all-powerful Communist Party.) Even then, informal surveys showed that about a third of Cuba’s population still held a favorable opinion of him.

It was something Castro’s foes from Washington to Miami never quite understood: Despite his dictatorship, a core of Cubans maintained a spiritual bond with his dynamic cult of personality and the feeling of national pride and sovereignty he gave them.

A Loss of Relevance

Castro bore little of that attachment to his own family, despite siring nine children. Nor did he have much of a private life, often moving from house to house in Havana out of fear for his security. His first wife Mirta divorced him in 1955. They had a son, Fidel, who has served as a Cuban government official. Fidel had five other sons with a second wife, Dalia Soto; another son and two daughters from three affairs. One of the daughters, Alina Fernández, defected to the U.S. in 1993 and is a vocal critic of the Castro regime.

Fidel’s one notable indulgence was fine Cuban cigars, though he quit those in his old age. And like those famous Cohiba smokes, Castro in his last years was little more than a symbol of a bygone era. Though the left still lionized him, 21st-century Latin American liberals began to look not to radical Castro wannabes like Chávez, but to moderates like former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Castro tried to remain relevant by penning rambling op-eds on world affairs. But by now he was a geriatric convalescent in a track suit, not the dashing subversive in fatigues. And he faced the one thing he hated more than being contradicted: being ignored.

Because Spain fought so hard in the 19th century to hold on to Cuba, the island in the 20th century harbored an exaggerated sense of its geopolitical importance. So did Castro, and so did his exile enemies. It’s why even their unimportant fights were so furious, including the 2000 custody battle over Elián González, when the exiles and Fidel turned a 6-year-old boy into a political football.

With Fidel Castro gone, those fights continue under Raúl, but they won’t be as fierce–especially since the U.S. and Cuba restored diplomatic ties in 2014, a move Fidel grudgingly accepted with the caveat, “I don’t trust the United States.”

Today the debate is focused more on social-media dissidents like Cuban blogger Yoani Sánchez. Raúl himself is 85, and he’s had to reverse many of Fidel’s dogmas, like a ban on private real estate sales, to keep the regime breathing.

When Raúl dies, it’s doubtful the revolution will last long without a Castro at the helm. In fact, in many ways it already ended, years ago. If we didn’t notice, it’s because the more heroic picture of Fidel Castro was too deeply burned in our flawed imaginations.

Listen to our special coverage of the aftermath of Fidel Castro's death here: