COMMENTARY

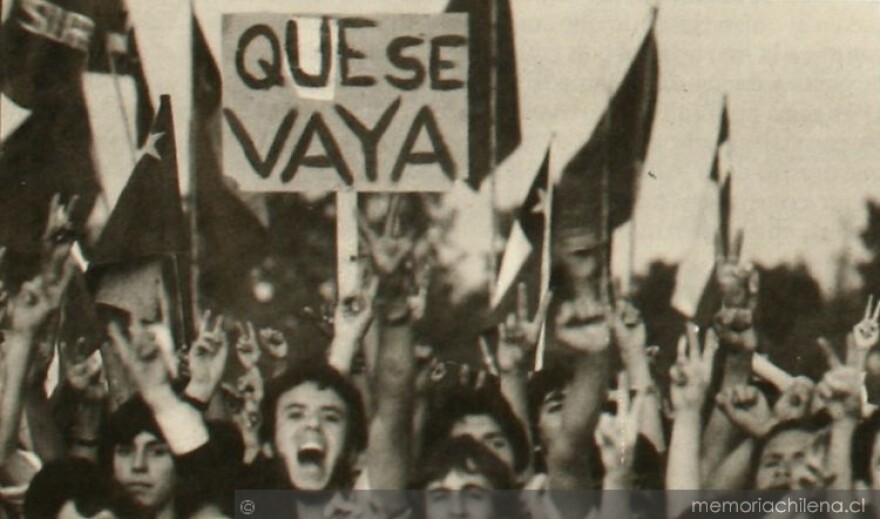

When right-wing military tyrant Augusto Pinochet ruled Chile in the 1970s and 80s, a then-democratic Venezuela gave refuge to Chilean opposition exiles who'd been targeted for prison or “disappearance” under his brutal dictatorship.

So it’s fitting now that Chile is providing sanctuary to Venezuelan opposition leaders hounded by the kangaroo justice of their country’s brutal left-wing dictatorship. Like Freddy Guevara, vice president of Venezuela’s opposition-led National Assembly – recently dissolved by the socialist regime – who took asylum in the Chilean ambassador’s Caracas residence this week.

But like anyone who wants democracy restored in Venezuela, I’m hoping the Chileans offer politicos like Guevara more than shelter. I hope they give them advice.

READ MORE: Trump Did the Alt-Left a Big Favor, Too. But Not the Alt-Left You Think

A generation ago, the Chilean opposition toppled its dictatorship – something Venezuela’s opposition has failed at. That looked painfully apparent last month when the regime routed the opposition in regional elections.

After covering Latin America for three decades, I’ll be the first to concede that ousting entrenched, tin-pot autocrats like Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro isn't easy. And I will grant that Chile in the 1980s and Venezuela in the 2010s are in many ways different situations.

Like anyone who wants democracy restored in Venezuela, I'm hoping the Chileans offer Venezuelan opposition leaders more than shelter. I hope they give them advice.

But in many ways they’re similar. So there are lessons the Venezuelan oppos should learn from their Chilean predecessors if they want their oil-rich nation to escape the political repression and economic ruin that Maduro and the ruling Chavistas have nailed into place. Here are some important ones los chilenos need to share:

•Grow up and unify. When Pinochet’s foes formed their Democratic Alliance, it was the unlikeliest of coalitions – conservative Christian Democrats sitting with radical communists.

“They didn’t like each other, but they worked together,” says Frank Mora, head of Florida International University’s Latin American & Caribbean Center.

Not so with Venezuela’s opposition coalition, the Democratic Unity Table, or MUD. Its candidates did bury the government in National Assembly elections two years ago – a voter response to Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis. But since then the MUD has once more split among factions, agendas, strategies and egos.

“There’s too much infighting,” says Mora. “Too many people thinking they should be the leader. The regime has taken advantage of that and played them off each other.”

RIGGED RING

●Take part in the process – even if the process stinks. In 2005, Venezuela’s opposition leaders boycotted Assembly elections and handed the legislature to the Chavistas on a silver platter. It was their biggest blunder. So what did many of them petulantly do last month? They boycotted the regional elections – and helped hand the socialists 17 of 23 state governor seats.

Javier Corrales, a Latin America politics expert at Amherst College in Massachusetts, calls that “the abstentionism trap.”

“Chile’s opposition fought that tendency,” says Corrales. It realized that you don’t shine a spotlight on a dictatorship’s rigged boxing ring by standing outside it. By staying and slugging, the Alliance got Pinochet to agree to a plebiscite in 1988 on whether he should leave power.

•Don’t lash out at the regime’s supporters – reach out. One of the Alliance's biggest challenges was winning over Chile’s sizable number of Pinochet backers. Anyone who’s seen the 2012 film “No” recalls that it did that not by making them feel lousy about el general, but by making them feel great about what would replace him.

“The MUD hasn’t done that effectively enough,” says Mora. “Most Venezuelans may not like the regime, but a lot of them still don’t look at the opposition as a force worth fighting for on a national level.”

And that has a lot to do with the opposition’s lingering image as a club of affluent, east Caracas denizens out of touch with the poor, west Caracas barrios that symbolize the Chavistas’ base. Until the MUD puts forward a leader who dispels that aura, its own movie will keep ending badly.

●Reach out harder – and smarter – abroad. Like Venezuela’s dictatorship, Chile’s was military-backed. “But when Pinochet’s generals saw how firmly the Alianza had the international community and especially the conservative [U.S.] Reagan Administration behind it,” says Corrales, “they forced him to accept his plebiscite loss.”

The MUD is getting better at selling its cause abroad. But it needs to learn a lot more from the Chileans. Starting over coffee this week in the Chilean ambassador’s kitchen.