The problem in the southern Indian River Lagoon is Lake Okeechobee.

An abundance of polluted water from the state’s largest lake is turning the lagoon’s normally aquamarine water brown and murky and endangering oysters, seagrass and other marine life.

The Lake Okeechobee water spreads across the Indian River Lagoon like a shadow. From the sky the boundary between dark and aquamarine is clear.

Chuck Mitchell stands on his dock as the water rushes past. He is angry.

“Ever have to flush your toilet twice? It looks like the first time. It’s that bad.”

Mitchell is a Stuart homeowner on the St. Lucie River, one of the waterways connecting the lake with the lagoon. Normally he enjoys sailing and swimming but not lately. He points to a large boat heading up the river.

“The bow water coming off of it should be blue. If you go down to the Keys it would be blue or the Caribbean. But what you see is a brownish-gray. That’s not the normal color of ocean water. That’s the normal color of Lake Okeechobee water.”

Since January more than a half-billion gallons daily have gushed from Lake Okeechobee through the St. Lucie River into the Indian River Lagoon as a wet winter pushed the lake to its highest level in a decade.

Mark Perry walks along the boardwalk at the river’s edge in downtown Stuart.

“The city of Stuart, for instance, uses about 6 million gallons a day. So that’s a lot of water going past here and going out to the Atlantic Ocean and kind of being lost.”

Perry monitors the lake and lagoon for the Florida Oceanographic Society. He eyes the river’s brown water, colored by the silt and sediment it carries from the lake.

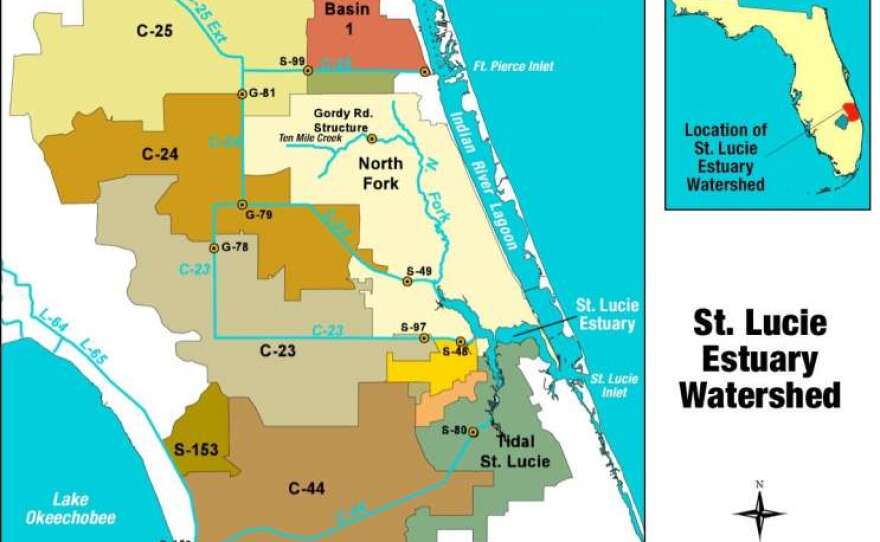

The water’s journey begins in central Florida. Historically the water flowed slowly into Lake Okeechobee and then continued south through the Everglades as wetlands cleansed the water of pollutants. Now a series of man-made canals sends the water rushing toward the lake and then much of it east and west through the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers rather than south.

The water that ends up in the Indian River Lagoon then drifts through the St. Lucie Inlet into the Atlantic Ocean. It is not responsible for the northern lagoon’s algal blooms and die-offs. But Perry says in the southern lagoon the water especially threatens oysters and seagrass.

“It also is damaging from the nutrient standpoint. In other words we get so much nitrogen and phosphorus in these discharges that we’re afraid if the water temperature comes up a little closer to 80 degrees and all the sunlight we might start to see algae blooms.”

“There were signs like right here on this beach and in every park all over Martin County and parts of Saint Lucie County that said, Don’t touch the water. Toxic algae.”

Not far from Stuart, Sewall’s Point Commissioner Jacqui Thurlow-Lippisch stands on a sandy shore of the Indian River Lagoon where she played as a child.

Toxic algal blooms in 2013 prompted advisories that people with respiratory conditions take extra precautions. Sailing camps were canceled, and a fishing show abandoned filming. Thurlow-Lippisch says the tropical playground she had grown up with is vanishing.

“People came to paradise because we come to paradise, but unfortunately sometimes when we come to paradise we turn it into hell.”

Like many she fears water flows from Lake Okeechobee will continue to hamper the lagoon’s recovery. And with the summer rainy season ahead she worries that another toxic algae bloom will further harm the health of the Indian River Lagoon.