Gregory Bush has been involved in studying and looking into the best ways south Floridians can move forward with plans for better management of public spaces in Virginia Key. He looked at the history of the region and how Miami has struggled with the best course for it in his new book, "White Sand, Black Beach." He will be discussing his work at this year's Miami Book Fair. I asked him where he found inspiration for this project.

It comes originally when I first came to Miami doing some oral histories of elderly African-Americans and then branching out over time and then getting really interested in Virginia Key as a public space and getting more interested in time in the waterfront and I could begin to see a lot of the problems of the entire downtown waterfront and then basically coming to the conclusion that I'd collected all these documents for so many years in relation to all these issues, I should put it together for a book. Then the National Park Service asked me to do a study of the viability of Virginia Beach as a national park. And so that started it. I did more oral histories and then I decided to add some personal elements, because I learned stuff about civic activism in the process. So it's both a history to some degree of the civil rights movement and more particularly kind of the politics of waterfront development.

How would you describe to people who don't know that history, the role Virginia Key played in the areas history?

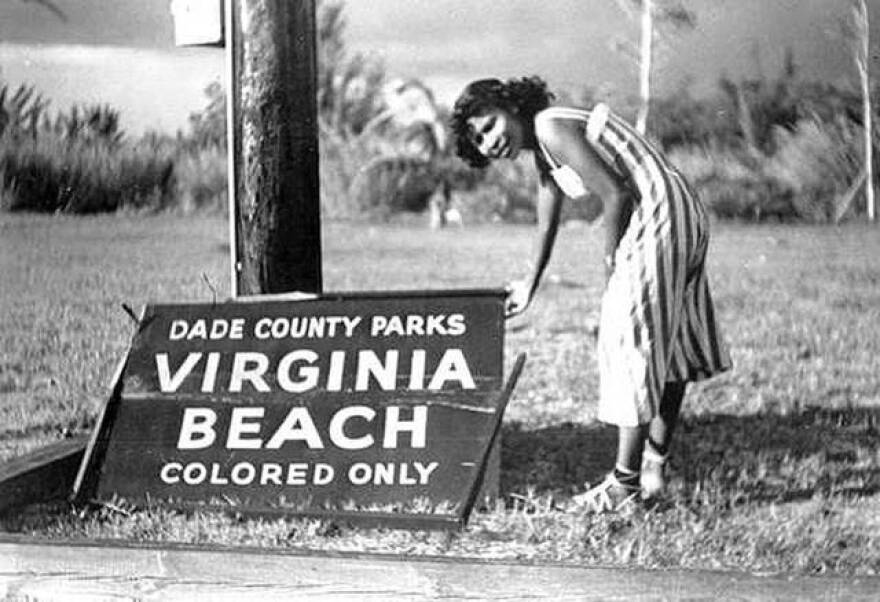

Well people need to understand that legally African-Americans, people from Bahamas etc. could not legally swim in Biscayne Bay before 1945. And in May of 1945 at Haulover Beach, there was the first essentially post-war civil rights demonstration led by Lawson Thomas, who later became the first black judge in the south. And it essentially was the final push to the city, the cops, or the county commission to allow the first so-called Black Beach.

So it was then a segregated beach out of Virginia Key. You only get there by boat in the early days, till 1947 when the causeway was built, and then it became an all African-American so to speak beach. And it became central to the community life from what I've seen from a lot of the interviews that that we did, and there were religious services there, all sorts of social happenings there. Martin Luther King and a lot of prominent people used to go there.

So it is a unique place in the south from roughly the late 1940s until the 60s when it became desegregated, and then that's a whole different story of what happened then and how people came together in 1999 to try to take it back when the city was all set to lease it out and sell it off for upscale development. And we said no, this should be preserved and enhanced as a public space so a lot of people became really interested in the value, (because) public spaces are going away around our waterfront.

This is South Florida and this is a developer's paradise -- how didn't that area not turn into high rise condos?

Research, organization, and media attention. A number of us came together from different groups, African-American and environmental groups and others interested in the island. Mabel Miller being a classic one going back in time and basically working together in a group going before endless meetings and boards and making our case. And then having done the research looking at the laws, we found for example there was supposed to be a parks advisory board for the city, and that didn't even exist. So just the research itself, I think, produced a lot of interesting results.

What's been the struggle all these years in trying to figure out what's the best decision for this area considering how fast things can move?

What you need to understand that Virginia Key is about a thousand acres and it has all sorts of different jurisdictions over it: the county land, the city land, there's protected land, wastewater treatment plants out there, there's Rusty Pelican Restaurant that most people know, the research facility. No one lives on Virginia Key so there's no constituency in terms of that. And then there's the Marine Stadium area that has a huge constituency of people that care about preserving it; enhancing it, reviving it, et cetera. And yet if you go take a look at that now. it's a bunch of parking lots around it.

To me it's a disgrace what's happened even though I understand different political interests and economic interests with boat show interest etc. and yet somehow I think what we're supposed to be, a park, has turned into a parking lot and you know I think it's something of an abomination.

The beach was used by the African-American community for some time. But after desegregation, what happened?

It became central to the community with a carousel, with a little train, with a food concession building, which are all still there by the way and have been revived, but by the 1960s when desegregation set in, anybody could go to any beach. And so it basically in many ways became less popular, and was arguably, over time, set up for failure and even to be sold off in 1982 to the county, which owned it and gave it to the city of Miami with deed restrictions to be used for park purposes only or it would revert back to the county.

The city of Miami promptly shut it down and it essentially was shut out from the public from 1982 or three to 1999, when a lot of this came in it was used for target practice, movie sets, stuff like that. So here is a public space, even with deed restrictions, that were very clear, and no county or city official followed them. And so a lot of the so-called civic activists got involved and said - this is not right. And then to try to transfer it to a private developer to put some upscale resort there, which is essentially what was in the works.

Why do you think that for so many years it almost seemed like public officials kept their hands off?

Well first of all, it's between Key Biscayne and Miami, as you said people don't know about it. So there's not much active knowledge about it or interest in it.

In 1963, when the Marine Stadium was created, there were boat races, people were going out to concerts and all sorts of stuff at the Marine Stadium basin. But again each space is different.

I would argue with a couple of exceptions where we're looking at holistically at the entire island, there wasn't even a really good city of Miami master plan. A lot of us pushed to have that done too.

Here's an excerpt from the book read by Gregory Bush.