Andrea Castillo spent the summer of 2012 working on her mom's campaign for the Miami-Dade County School Board.

But when Susie Castillo was sworn into office that November, Andrea wasn’t there to see it. The 21-year-old died in a car accident a few weeks before.

Nearly six years later — after Castillo’s first term and a successful re-election election campaign — it’s impossible to examine her work on the school board and in the community without seeing Andrea everywhere.

Because of her daughter’s dream of becoming a teacher, Castillo started a foundation that awards scholarships to prospective teachers who attend the colleges where Andrea had enrolled. She helped found a first-of-its-kind teaching academy at Andrea’s high school.

Andrea’s best friends work for Castillo at the school district and the foundation.

She has also worked to boost access to mental health care in Miami-Dade schools, especially for children who are dealing with grief and loss.

Castillo's focus both causes her pain and brings her solace, as she is constantly reminded of her daughter's death but feels like she's doing something to honor her life.

“It makes me happy that her legacy continues,” Castillo said. “This is one of the few things that really makes me smile, makes me feel good. And it’s not because of what I’m doing. It’s because she lives on.”

ANDREA AS HER 'COMPASS'

Right after the accident, Castillo was getting lots of calls from reporters. Her attorney suggested she hold a press conference so she could address the media all at once.

Castillo had just been elected to the Miami-Dade County School Board — she hadn’t taken office yet — when she lost her daughter.

Andrea died a few days after her 21st birthday, in October of 2012. She suffered severe head trauma when her boyfriend’s SUV collided with a Hialeah police officer's car. Both the on-duty cop and Andrea’s boyfriend, Marco Barrios, survived, although Barrios endured severe injuries that left him in a wheelchair for months after.

The ordeal was painfully public. Castillo and Barrios sparred with the Hialeah police department over what caused the crash — questions about whether the police officer was speeding, whether Barrios ran a stop sign, whether the couple was wearing seatbelts. Ultimately, Castillo was awarded a nearly half-million dollar settlement from the city of Hialeah because the police officer, who had broken bones, had been airlifted to the hospital, while her gravely injured daughter was taken in an ambulance.

That press conference, on Halloween in 2012, was a blur.

“My mind and my heart was in shock. I couldn’t think straight, I couldn’t put words together,” Castillo said. “I was functioning on automatic without thinking about anything that was going on around me.”

One reporter asked Castillo: Would she serve on the school board after all?

“Honestly, that was the one question that I remember being asked,” she said. “Because it hadn’t even crossed my mind. The only thing that was in my mind was that I had lost my daughter, and I had to do something for her."

Andrea had wanted Castillo to be on the school board so she could help teachers. The young woman was studying to be a teacher herself, and she imagined being able to share her perspective with her mother during her first years in the classroom. Andrea worked all summer to help her mom get elected — appearing in a campaign ad, knocking on doors, rounding up her friends to volunteer.

“I felt that, somebody has to complete her work,” Castillo said, “or at least move her work forward.”

Castillo represents district 5, a western chunk of Miami-Dade County that includes Doral and Miami Springs. Running unopposed, she won a second four-year term in 2016.

Before Andrea died, running for the school board seemed like a logical next step in Castillo’s career, her son, Kevin, said. Castillo had spent years working as a school district administrator and later as chief of staff to the mayor of Doral.

Now, it feels more like her purpose, Kevin said — “what she’s compelled to do as a person.” Kevin was 17, a senior in high school, when he lost his big sister. He’s 23 now — older than Andrea was when she died.

“It feels almost obvious to me,” Kevin said. “She’s using my sister’s passing … as a compass. My sister is pointing her in the right direction."

SCHOOL BOARD BRINGS CONSTANT REMINDERS

Castillo’s grief propels her forward. But it also slows her down.

Her work at the school board is “overwhelming at times,” said Arlene Diaz, who is in charge of teacher certification at the Miami-Dade school district.

Diaz is Castillo’s best friend; they’ve known each other for two decades and went to college together as adults.

“When she hears stories of parents dealing with their children, it emphasizes that her child is not there,” Diaz said.

During her time in office, Castillo has championed mental health care for students. In 2016, she authored a resolution prompting the district to train teachers in how to support grieving students. Last year, she proposed requiring principals to strengthen their efforts in hiring enough counselors for their student populations.

Her motivation is twofold: She thinks of kids like Kevin, who was in high school when Andrea died. She worries she didn’t support him enough then, because she was in shock herself. She hopes other kids struggling with loss can get help at school.

Castillo also thinks of her brother, Evelio Vicaria, who was schizophrenic and struggled with drug addiction. He hung himself in 1984 when he was 27.

Two months ago, Castillo brought forward another proposal that would better equip schools to address the needs of grieving students. It came about five weeks after 17 people died in the Feb. 14 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in neighboring Broward County.

And yet another tragedy hit close to home: the bridge collapse at Florida International University that killed six people, including an 18-year-old student. That day, March 15, was Castillo's first day on the campus at a new job as director of alumni relations.

When disaster takes lives, “the pain comes back,” she said. “You never let that go. You always relive it.”

She said she relates to any parent who loses a child.

“It’s just not natural to lose your child. And it’s not something that you ever heal from. … You never heal,” she said. “You just learn how to live a different life.”

One source of comfort: her daughter’s friends — some of whom she has asked to work for her as staff members at the school board and board members for the Andrea Castillo Foundation.

Every year since Andrea died, Castillo has held a memorial to commemorate her birthday, Oct. 18. Andrea’s friends — now in their mid-twenties, dealing with careers and relationships — come to the beach, catch up and celebrate her.

At last year's memorial, in Sunny Isles Beach, Kevin blew up balloons with LED lights inside them — to make them glow. Using markers, everyone wrote notes to Andrea on the balloons and then released them, while singing, “Happy Birthday.” Castillo called the balloons “messages to heaven.”

Karla Moran — a friend of Andrea’s who worked as Castillo’s administrative assistant at the school board for a year and a couple months — drew a flower on her balloon. “All beautiful things remind me of her,” she said.

Andreina Espina was Andrea’s best friend since seventh grade. (Back then, Andrea went by “Andii,” signing her name with a smiley face connecting the dots on the is.) Now, Espina has a different position: Castillo’s chief of staff.

Espina studied international relations at FIU and began working at a law firm after she graduated. She became Castillo’s scheduler in 2015. Since, she has since moved up into the top staff position.

“I’m not just her chief of staff,” she said. “I am also taking care of her for Andii.”

To Castillo, Andrea’s friends are so important.

“It’s an unspoken understanding that we have. They fill in when I can’t. They say the words, they understand what I’m feeling, when I can’t do that for myself,” she said. “So that’s why I brought them in.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q6I-1pZhz3U

A FOCUS ON FUTURE TEACHERS

In May 2012, a couple of months before her election, Castillo made a campaign video marking teacher appreciation week.

Her face was in the middle of the frame. Silently smiling next to her, on her right, was her mother, May Garcia-Clissent. On her left, Andrea.

“Teachers have always been at the center of my family,” Castillo said, explaining that her mother had taught in Miami for more than a quarter century.

“And now my daughter, Andrea, is following in her grandmother’s footsteps, on her way to also becoming a teacher.”

Garcia-Clissent, 84, was Andrea’s inspiration to pursue a career in the classroom. She came to Miami from Cuba in 1961. Then, she was 25 and had three children; Castillo was only six months old.

She had been a kindergarten teacher in her home country, but her credentials were not accepted here. So she worked as a “Cuban aide” at a school in Hialeah, helping other immigrants register for school and acclimate.

She ultimately got a bachelor’s degree and went back to teaching kindergarten — which she says she was born to do.

When Castillo was pregnant with Andrea, she hoped the new baby would provide her mother with some healing, since Garcia-Clissent had lost her son to suicide. Castillo told her mom the baby was for her.

“This was the way that I could help her find some kind of peace,” Castillo said.

To Andrea, Garcia-Clissent was Abuela May. For much of Andrea’s life, they lived just a couple of doors down from each other. Andrea would stop by her grandmother’s house after school and invite her friends over for dinner. When Andrea’s mom and grandmother would argue, Andrea was the mediator.

“I think of Andrea every day. I pray for Andrea every day,” Garcia-Clissent said during a recent interview in her Doral home. “I cannot show my feelings to Susie, because I know that Susie is hurting, and I have to be strong for her. But half of my heart is gone.”

A year after the car accident, Castillo started a foundation in her daughter’s name. The beneficiaries: prospective teachers.

When Andrea died, she had just finished her studies at Miami Dade College and was about to start classes at FIU. Castillo started the foundation in 2013, creating $25,000 endowments at both schools. So far, 18 students have won $1,000 scholarships.

Geraldine Perez was one of the first recipients, and it’s already her fourth year in the classroom. She teaches elementary students at a charter school, the Doral International Math and Science Academy.

She said the scholarship got her to graduation at FIU. During her last semester, she was student teaching, and she wasn’t able to hold a job in addition to the intensive assignment. She was tight on money.

So she applied for the scholarship.

“If it weren’t for that, I probably wouldn’t have been able to finish that last semester,” she said.

“My parents came from Cuba. I’m first generation — first in my family to go to college,” she said, starting to cry. “So I get a little emotional, because that’s why they came here. To be able to finish was a beautiful, beautiful experience.”

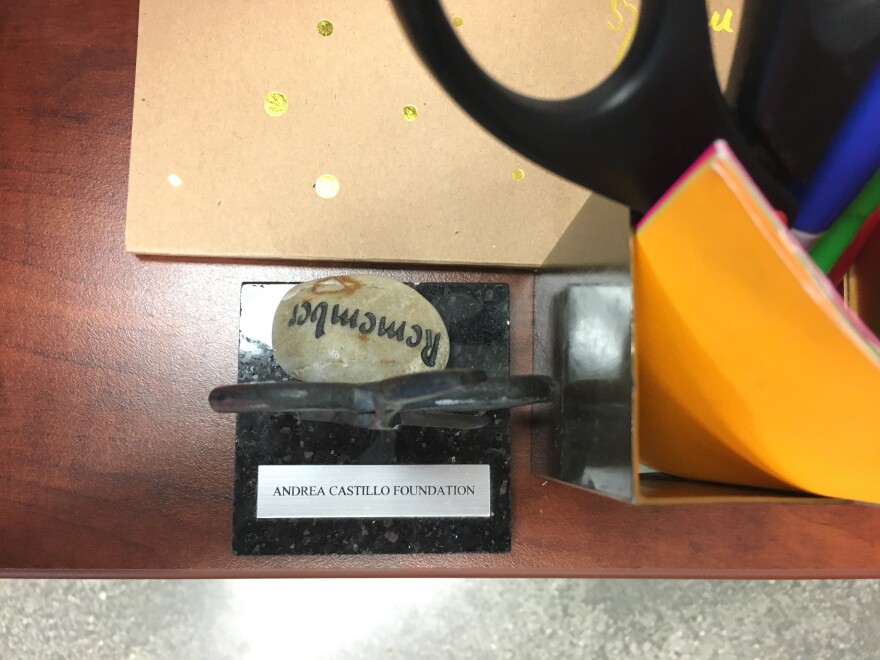

Castillo first met Perez at a ceremony where the scholarship recipients received their awards. Castillo gave the winners trophies in the shape of apples.

A while later, they saw each other again — this time, at a grand opening event for the charter school where Perez works.

“I saw her cutting the ribbon with all the big people here in Doral: the city councilman, and the mayor was here, too,” Perez said. “And the whole time, I’m like, ‘Oh my god, that’s Susie!’”

Perez approached Castillo asking, “Do you remember me?” It took a second for Castillo to place her. When the school board member realized who it was, she started crying.

“I was overwhelmed. I was like, ‘What? Wait!’” Castillo said. “I was at a ribbon cutting. I wasn’t putting the two together.”

Perez told Castillo she had the apple trophy sitting on her desk in her classroom. Behind it was a rock with an engraving: “Remember.” The young teacher said looking at the keepsakes reminds her of how she got to where she was — with the help of Andrea’s family.

Castillo recounted the anecdote with a mix of joy and sadness.

“It’s beautiful to see that [Andrea] has made such an impact in this world, and there are so many people’s lives that she touched, and that she lives on through all these people,” Castillo said. "But it’s painful, because it reminds me that she’s not here.”

ANDREA'S 'LEGACY': A TEACHING ACADEMY

Next year, the first class of seniors will graduate from the Andrea Castillo Teaching Academy at Ronald W. Reagan Doral Senior High School.

Castillo helped start the program three years ago at her daughter’s alma mater. Students who are interested in careers in education can dual enroll at the high school and FIU, earning up to 12 college credits before they graduate. Participants also tutor their peers and complete a student teaching assignment in an elementary or middle school as part of the program.

“It promotes a desire and a hunger to teach,” said Karla Lopez, the academy’s director.

Castillo visited the school late last year. She knows the junior class well but hadn’t met the freshmen yet.

“I’m your school board member. I was elected by your parents,” she told the class of ninth graders. “I’m Andrea Castillo’s mother, and I’m so happy to be able to meet all of you.”

Students there know why their school was founded.

“This academy is not only an academy. It’s a legacy, and it’s a movement,” said Cristian Cancino, a junior.

“It’s a legacy, because we’re carrying someone’s dream. We’re carrying someone’s aspirations,” he said. “And it’s a movement, because what happens inside this classroom is not something that will stay within the four walls of this classroom. But it happens within the four walls to affect what’s out there.”

The school has already made an impact outside its four walls: It has inspired plans for another teaching academy at a high school in Coral Gables.

In the school's courtyard, there's a mural honoring Andrea that was painted by Tony Mendoza, a celebrated local artist. Mendoza also decorated the outer walls of the school board building in downtown Miami.

The artwork shows a girl’s hand holding an apple and a pencil. On her wrist is a tattoo, an ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic symbol that looks like a cross with a loop on top. It means eternal life. The girl is wearing a green bracelet that says “Andii” — Andrea’s nickname.

When showing off the painting, Castillo held up her own arm to reveal a matching tattoo — the mother and daughter pair got it together. She wears the bracelet.

Castillo said it’s difficult for her to visit the school, because it reminds her of the opportunities Andrea never had. But, she said, the students’ devotion is humbling.

“It’s really nice to know that she made such an impact in this world and that she continues to make an impact,” Castillo said.

Castillo has focused on helping teachers with Andrea in mind. But as it turns out, her work may affect her son, as well.

Kevin started college with plans of becoming an engineer. But recently, he changed his major.

Now, he’s headed for the classroom.