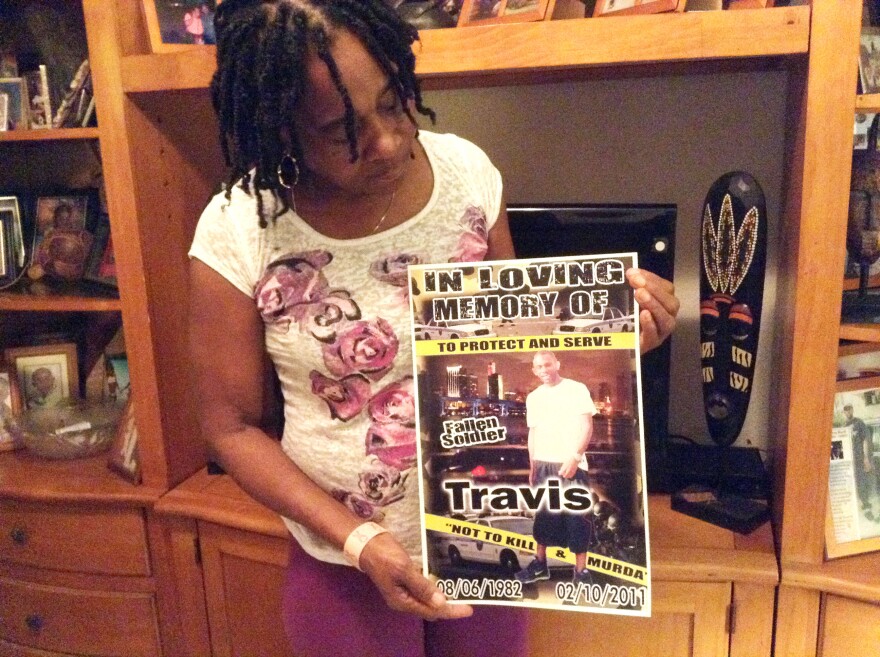

Sheila McNeil says she still holds hope that the Miami police officer who killed her unarmed son three years ago will one day be held accountable.

Prosecutors cleared Officer Reynaldo Goyos, who believed Travis McNeil was reaching for a gun when he shot him during a traffic stop. Goyos was fired in 2013, only to be reinstated with back-pay. But there’s one agency left with an open case: Miami’s Civilian Investigative Panel, which reviews cases of alleged police misconduct.

The independent watchdog has yet to close its inquiry — nearly two years past its own deadline.

“I feel like I don’t have any justice,” says McNeil. “They say they’re supposed to work for the people, but I don’t know what they’re doing.”

The problem with the McNeil case is all too common, according to a joint Miami Herald-WLRN review of five years of Civilian Investigative Panel cases. Once held up as a national model for police oversight, the agency has stumbled. Disorganization, budget cuts and internal power struggles have delayed scores of cases, while countless others have been rubber-stamped.

Among the findings of theMiami Herald-WLRN review:

- Budget cuts and infighting have crippled the agency, leaving it for months with just one investigator. Inter-office relationships have grown so strained that the CIP’s volunteer board wants to pay the agency’s attorney $175,000 to go away.

- Cases regularly exceed the CIP’s 120-day deadline for resolution. City ordinace says that cases that run past the deadline must be closed without any finding of fault. In at least 128 instances it took more than 200 days for the CIP to resolve a case. High-ranking administrators disagree about how to apply the deadline.

- There are many cases where it is unclear how long it took for resolution because case files are missing the start date for investigations. Records are kept haphazardly, and the CIP can’t provide accurate statistics. Some case logs are missing altogether.

- About half the cases the agency received were administratively closed without investigation.

- The subpoena, arguably the CIP’s most powerful tool, hasn’t been issued for an officer to appear before the agency since 2009. Administrators can’t say how many have been issued.

Following a Miami Herald article documenting racism allegations and internal sparring, city leaders recently launched their own inquiry of the CIP. A draft of a report crafted by a review committee states the agency was slow to resolve cases and blames vague governing policies, a confusing power structure and budget cuts for recent controversies.

“The reason the stuff hit the fan is the budget collapsed from under them,” said committee member Clarence Dickson, who served as Miami’s first black police chief.

Activists who fought for the CIP’s creation years ago, however, say the agency’s problems are the fault of its over-reaching independent counsel, former assistant city attorney Charles Mays. A coalition including the ACLU and NAACP has asked for his ouster, though the city’s committee found he isn’t to blame for the agency’s issues.

“I did absolutely nothing wrong,” Mays said in an interview. “My client, the CIP, did absolutely nothing wrong.”

Voters overwhelmingly approved the creation of the CIP in 2001 as an amendment to Miami’s charter, following a series of fatal police shootings of black men and the indictment of 13 cops accused of covering up problematic shootings by planting “throw-down” guns on suspects.

The public demanded that an independent agency investigate allegations and suspicions of Miami police misconduct. Early on, the CIP examined the department’s heavy-handed approach to Free Trade Area protests, and former Chief John Timoney’s free use of a Lexus SUV.

Today, operating on a city-funded budget of $564,000 budget — about half of what is once received — the CIP hires investigators to pursue their own leads and interview victims, witnesses and officers. A volunteer panel of 13 appointees then makes recommendations on whether city and police officials should follow through with discipline.

Each year, the agency gets between 150 and 400 cases to review and investigate. But the CIP had dozens of open cases as recently as this year, and just one investigator. In the past the agency has employed three. Executive Director Cristina Beamud wrote this month in a letter to the review committee that she found a disheveled office with “files in disarray” when she was hired in December.

Beamud, a former investigator and and prosecutor with experience in police oversight, said she found a filing cabinet with cases that were administratively closed without explanation and apparently left by the wayside.

“There was no evidence that anyone had done any work on these files for years, even in the firearms-discharge cases,” she wrote. “They included six of the seven shooting deaths that occurred in 2010 and 2011. They included an in-custody death.”

One open case was filed in 2009 by former Broward County prosecutor Nicole Alvarez. She claimed that while driving south on Interstate 95, two Miami officers sandwiched her between their two patrol cars. When she tried to switch lanes, the officers continued to “play a cat and mouse” game with her for nearly 30 minutes during her commute.

When it was over, they pulled her over and wrote Alvarez a ticket for “following too closely.”

An investigative case log shows that nothing has been done in five years to bring closure to the case, which sparked a lengthy lawsuit.

Dozens more have likewise languished, including some of the seven deadly police shootings of black men that led the U.S. Department of Justice to conclude Miami police had a systematically brutal approach to policing the black community. The American Civil Liberties Union, which launched the CIP probes with a complaint and is supposed to be kept in the loop, says four of the seven cases remain open and the three that have been closed ran far past the city’s own rules.

Julia Dawson, an attorney who co-chairs the ACLU’s police practices committee, reviewed the shootings. She said none of the cases included a legally required written notice from Mays for an investigation to begin.

“For the last five years, the CIP has been little more than window dressing,” Dawson said.

Perhaps the best way to explain the CIP’s dysfunction is to note that while the agency was tasked with watching police, no one truly was watching the agency. Miami taxpayers pay about $125,000 a year for Beamud. Mays, who works part-time, earns $132,000 a year. Both are chosen by the CIP panel, but Mays answers only to Miami’s city attorney, and Beamud answers to the city manager.

Mays and Beamud each want the other gone. Tensions have spilled out into public hearings, during which allegations of racism have been voiced after two of the three CIP investigators were either fired or quit under Beamud’s short tenure. The two investigators were African-American.

Meanwhile, no one seems to answer to the board.

“The people who are supposed to be working for them really don’t have to listen to anything they say,” said Dickson.

Beamud says CIP’s problems date back years. She argues that she’s bringing legitimacy back to the office, although during her short tenure she has been accused — and cleared — of penning notes with racial epithets. Twice, a majority of the CIP’s board voted to fire her, but found it could not because she answers to the city manager.

Mays, the CIP’s contracted attorney since 2005, has been a controversial figure for years. The agency’s last full-time chief investigator accused him five years ago in an exit memo of becoming a “gate-keeper” for cases by abusing laws that allow him to choose which cases would move forward and whether subpoenas would be issued.

Mays has come under fire by the ACLU and the NAACP, which claim he interferes with investigations and gives the panel questionable legal advice. The CIP’s chairman has also criticized Mays, and investigator Elisabeth Albert provided the city’s committee documents which she said proved he whitewashed two of her investigations.

Mays brushed aside many of the allegations and concerns as “distorted and false,” and says he has done everything by the book. He will be cleared by the committee’s final report of any “malfeasance” or “misfeasance.” The committee said that, if anything, Mays went beyond his duties “to protect the city” when the CIP fired its former executive director, and opined that the agency’s cloudy laws and policies had led to the mess that has dragged the CIP down.

Still, the CIP panel wants to pay him $175,000 to leave. Commissioners have to agree to spend some of the money and they balked last week, in part because the agency just renewed his contract this year. City Attorney Victoria Mendez said she doesn’t support paying a “buyout,” which isn’t stipulated in his deal.

“There is no need to pay him $175,000 to walk away. There’s no contractual obligation to do so. I’m not recommending that,” she said.

Part of the problem: while the CIP’s board has moved to fire Beamud, members have never tried to remove Mays. Chairman Horacio Stuart Aguirre believes the agency can break even by paying Mays a buyout over two years and hiring an outside firm as legal advisor at a far cheaper rate.

“We’re better off paying Mr. Mays and having a respectful and friendly parting of the ways,” he said.

As the agency tries to fix its problems, it continues to deal with its past, including the confusing case of Travis McNeil, who after he was shot dead by Officer Goyos was found not with weapons but with two cell phones on the floorboard of his car.

When Goyos was fired two years ago, the CIP was supposed to close the investigation. But now that Goyos has been reinstated, the agency somehow finds itself with an open case, a past-due deadline, and an angry, grieving mother.

“It's sad because we look to these people to help us get closure and it’s not happening,” said Sheila McNeil. “It was a way for the community to get help. They can't help us. They can't help themselves.”