In a breakthrough that could lead to more enduring coral restoration work, scientists for the first time have been able track heat-tolerant coral near Florida’s crippled reef.

New technology allowed a team from the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School and Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium to replicate deadly heating events on shipboard tanks in a matter of hours, compressing natural bleaching events or lab experiments that can take weeks. That let the team conduct a reef-wide census in ocean nurseries, to provide a broader indication of where hardier coral can be found.

WLRN is committed to providing the trusted news and local reporting you rely on. Please keep WLRN strong with your support today. Donate now. Thank you.

Researchers say the work can be easily duplicated across the planet’s oceans, removing a hurdle that once bogged down the race to rebuild dying reefs.

“You can literally motor down the Florida Keys, picking up corals as you go and then measure their stress tolerance on board ship,” said Rosenstiel professor and coral researcher Andrew Baker, who co-authored the findings published Wednesday in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. “As you finish with one batch, you can then start with the next batch and pick up the next batch and within the space of really less than a week, you can do them all.”

Being able to identify the more resilient coral in oceans means researchers can take advantage of regular spawning cycles, when millions of eggs and sperm get released in vast clouds, to harness broodstock.

“Until now, we never really knew how much variation in thermal tolerance and heat tolerance there was among these different corals,” Baker said.

Researchers targeted the fast-growing staghorn coral that once dominated Florida’s reef tract and have been widely used to restore the reef. A September study found staghorn can double the power of reefs to weaken waves that erode the shoreline.

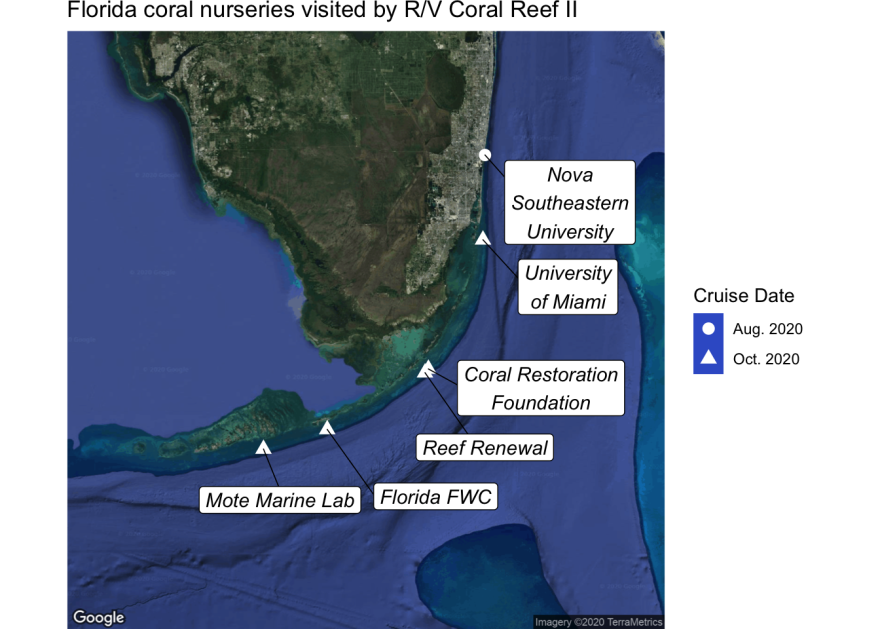

The staghorn were mostly wiped out by a disease outbreak in the 1980s and are now being grown in nurseries from the Keys to Broward County. Warming oceans driven by climate change have continued to leave them vulnerable. They are also the species widely grown in shallow nurseries along Florida’s coast and replanted to restore reefs.

“The big picture problem is corals are threatened by climate change all over the world. But here in Florida, we're sort of running out of corals,” Baker said. That means scientists after to rely more and more on nursery-grown coral, that being bred in inshore nurseries across South Florida considered among the largest on the planet.

After the planet’s first mass bleaching occurred in the 1980s, scientists began trying to unravel the complicated process that caused coral to spit out the symbiotic algae that live in them when waters become too warm. Without the algae, the corals starve and die. But bleaching isn’t uniform. Some corals harbor more heat tolerant algae — an issue Baker has been pursuing. But some just mysteriously do better, he said.

“Some corals, just like individuals in a population, are just better at doing some things than others,” he said.

Being able to more quickly identify those corals on a broader scale gives scientists a lot more information to work with.

“Typically, to measure heat stress, you have to run an experiment that might take several weeks. And to do this with all of the corals in all of the nurseries would just take a very long time,” he said.

Growing more heat-tolerant staghorn in nurseries means reef rescuers will be better armed to respond after the next bleaching event. In 2017, the last widespread bleaching event hit two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef. In 2015, a bleaching event that started in the North Pacific spread to U.S. reefs, impacting about 95% by the time it ended.

The survey also revealed that more tolerant coral aren’t just located in warmer waters, where they’re more frequently exposed to higher temperatures, but they were spread across the reef — which Baker said is good news.

“It means that the existing standing stocks of genetic diversity that are out there probably don't need to be aggressively moved around too much,” he said.

And the more different corals are around the better — because heat isn’t the only threat they face, he said.

“The more different types of organisms that are out there, the more the range of different strategies that they can pursue to sort of survive,” he said.

The next step in the research, Baker said, it to take it on the road and test it out on other reefs. The project was originally supposed to occur in the Bahamas, but the COVID-19 pandemic prevented that. Researchers now plan to repeat the work on the larger reef tract that also has a larger range of temperatures.

Baker says the ultimate goal is to explore how the corals in the two countries can help each other.

“Some of the most exciting next steps really are in the selective breeding side of things and in the international cooperation side of things,” he said. “If countries can really cooperate to share their genetic resources and share their corals and try to figure out how to build the most resilient network across the whole region, that's really where the future lies.”

You can read more stories like this one by signing up for our environment text letter. Just text “enviro news” to 786-677-0767 and we’ll send you a roundup of stories like this — and more — every Wednesday.